Model is Louis Puster III, photo by Caitlin Holden

The final three-day event of the Dust to Dust LARP campaign ran last weekend. Dust to Dust has been a part of my life since 2006, and even though it has to end, I still have a hard time believing that it is done. I’ll probably be writing a lot of retrospective posts about it, and I’m starting with one of the most different things that we did – and the one that has already seen the most borrowing by other games.

Ritualism

In August of 2007, in Livejournal, I was doing a bunch of semi-public design work for DtD. I posted the following:

The core of this idea comes from crossing Noumenon (a truly obscure tabletop game) and Puzzle Pirates.

I’ve been pondering a system for ceremonial magic that would require less Plot presence. This would allow your entire system of magic to be based more fully on rituals that have a chance of failure, but also allow player skill and character skill levels to affect the outcome.

Once they’ve completed their roleplay of the ceremony (the same point at which a card or bead draw would normally be made), the lead ceremonialist player receives a bag of dominoes. He draws a number of bones equal to his relevant skill level + 3. Each contributing ceremonialist draws one bone. Characters may commit various additional resources (mana or other components) to draw a larger hand. Characters keep drawing bones as they pose them. These dominoes are played collectively, with the goal of using as many pieces as possible. (Or completing as many squares as possible, to increase the challenge.) Any given ritual has a required number of successes; falling short of this has a backlash specified by the ritual, while success and exceptional success (an extraordinary number of successes, or playing the game in a more challenging way) also have stated outcomes.

There are probably some serious holes in this that I’m overlooking, but it’s basically LARPing with minigames that can be played solitaire. It can even be turned into a competitive game for contested rituals, as you simply use the same pieces to play a two-player game.

Thoughts?

With a lot of hammering and discussion, this turned into the Ritualism rules that we published on the DtD website. There are a lot of moving parts in these rules, and there are more complexities that become apparent in the spells. I want to break it back down to its component parts and talk about why some of these elements are useful; my goal is to make it easier for future games to borrow or hack these rules.

Throughout this post, anywhere that I use the first-person pronoun to talk about the design of ritualism, please understand that other staff members – especially Stands-in-Fire – and players made indispensable contributions and I am unintentionally hogging credit.

The central idea of the system is that domino bones are both your budget for spells and your physical tool for casting spells. Because I like Vancian magic (it’s okay to disagree with me, but neither of us are likely to convince the other of anything), this is about storing spell effects for later use, and having spellbooks crammed with spells that do narrow things. The other central idea is exploring ways to store complexity that you can resolve and move on. That is, you have complex resolution at a time of low tension, resulting in simple outcomes at a time of high tension.

To do this, we wrote ritual formulas and released them into play. Each ritual formula is composed of three parts:

- Flavor text

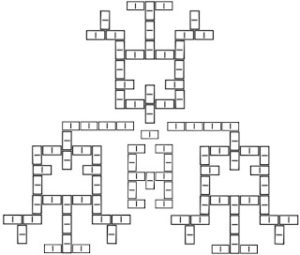

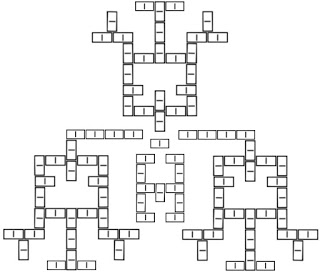

- Image of the rune you have to create with dominoes

- Rules text

The flavor text is important. It essentially serves three purposes: first, it showcases world lore (and you should always look for places to drop setting lore, so that names and events are just a little bit familiar when they come up somewhere else); second, it helps to communicate the theme that guided spell design (especially important if you’re doing something unusual); and third, it greatly enhances the collectible-cup feel of the magic – especially if you have a single story broken up across multiple spells.

Ritual Rune

The rune is the presentation of the puzzle. I created the majority of DtD’s ritual runes in Paint.NET, and over the course of the campaign I played around with different kinds of junctions that the casters would have to match. There are a few dirty tricks one can use here – such as requiring seven or more bones of the same value to touch, or requiring objects other than ritual bones to be part of the rune – but overall this is fairly straightforward. Many of the runes I created were vaguely pictographic, but low enough on granularity that you’d never get it if you didn’t already know what I was imagining.

Honest-to-God warning to others: it is harder to not draw sex organs than you think.

The rules text is where all of the serious moving parts are, so I’ll break this down further.

- Type is either Battle or Enchantment, with some relevant subtypes. It’s not 100% accurate to say that this is the determiner of whether you cast into your focus and activate later, or you have to apply the spell immediately upon ritual completion, but that would generally be a good use for this field.

- Duration is sort of a throwback of a field for 95% of spells – the duration was intrinsically obvious from the effect. The few cases where we did something unusual here (either shorter or longer duration) were fun content to create, though.

- Requirements is a rarely-appearing field that calls out any special conditions or materials you need in order to cast this spell. This information is usually repeated in the Description, below.

- Number of Bones is a count of the number of bones in the rune. If I had it to do over again, this field would also track the minimum number of bones you need in order to initiate the ritual, to save players from having to figure out 75% of anything and then round fractions in the course of play.

- Fatigue is the cost you pay on successful completion. This was one of our main controls on what ritualism was good or bad at, compared to other types of magic. Roughly speaking, one Fatigue is worth three mana. However, relatively few combat spells granted just one activation per casting, just to obscure cost efficiency a bit more.

- Obscuring cost efficiency is useful because it reduces the emphasis on One Best Way to prepare spells in a day (above and beyond the many possible goals one might have).

- Tagline on Cast is pure rules storage. We often improvised new tagline words into existence for this – wherever the ritual’s rules were really involved, this was likely to involve words not found in the rulebook. Because, famously, our Effects List was not long enough. (Ahem.)

- Tagline on Activation is more rules storage, but also helps you know whether the effect goes into your focus or is cast directly. Anything that goes into your focus should really conform to the rulebook’s Effects List, because – as part of our compartmentalized complexity – we don’t want you or your target to need to see the formula in order to resolve the effect. I’m sure we made exceptions, but few.

- Description is the core of the rules text. We worked with all kinds of different rules hooks and permutations, on which more later. Sometimes this was a single sentence, sometimes it was multiple paragraphs. We were always conscious of the need to write for clarity.

- Backlash is what happens if you fail to cast the ritual. We defined a few different kinds of failure, such as “getting Disrupted or knocked unconscious mid-casting,” walking away from the ritual, and so on. A tiny number of Backlashes were useful in their own right; other than those, I wonder how many castings got backlashed in the whole campaign. I saw one or two myself, but we made a lot of backlashes really godawful on the understanding that they would probably never happen.

Cooperative Casting adds a significant complication to these rules. Here again, we could only use rules like these because all of the serious complexity is stored in the caster’s spellbook, and the caster always has to have the formula visible to cast it. It does mean that two casters working together can cast a spell that neither one of them can quite yet cast alone. We wanted it to be possible to play a politician-wizard who pretty much chills out in the tavern and gets other wizards prepped for battle.

- Casters after the first contribute fewer bones according to (25 – the Fibonacci sequence value for their “rank” in the group). This was a very light and seldom-relevant brake on the power of very large groups, which in some situations could force you to add casters to get those last few contributions of bones. In the balance, this rule was probably not necessary.

- Multiple spellcasters mean that each takes less Fatigue, except that adding the fourth caster, and then the seventh, increases the overall Fatigue. This was to stop every casting from being nine people – we wanted to encourage three-person casting teams as the norm, with larger teams only when necessary. This rule worked out exactly as desired.

- The division of Fatigue works according to one of two schemes: master-apprentice or even-division. Even division splits the Fatigue as “fairly” as possible (given that the first-position caster almost always receives or controls the benefit), while master-apprentice advances the theme of senior wizards being selfish toward their apprentices. We deliberately didn’t include an option for the primary caster to eat the largest share of Fatigue and the apprentice just getting them over the hump to cast big spells, though I’m not 100% sure how clear this rule was to the PCs.

Removing cooperative casting entirely would make ritualism a lot less interesting, since cooperative puzzle-solving is fun. Fatigue distribution is a good place to serve other end goals, as Calamity’s Theurgy system does.

The whole system would have been less than worthless if it had required marshals for common use. Some specific spells required a lesser or greater spirit present in order to function, for reasons intrinsically obvious to those spells – for example, you can’t plane shift to the Realms Above without a marshal present, and without us doing some prep work. This did increase the burden on staff, but we planned around it to make it work.

Rules Hooks

Okay, everyone understands what I mean by rules hooks, I hope? It’s a situation in the game that is concrete and definable enough to be a trigger for something else to happen (or be able to happen) without anyone needing to adjudicate anything.

Some of our favorite rules hooks:

- The Orphans. No matter how powerful the ritualist, you never draw more than 25 bones from your bag. This is not negotiable. (This does more to enhance an illusion of failure chance than actually increase a failure chance.) Anyway, this leaves at least three bones in the bag. Some spells require you to pull out the last three bones and total up their pips. That value generates a random result between 3 and 33 on a table, with large or small values being very unlikely. This was an interesting randomizing agent that some players really enjoyed, and because of its random nature, we could do things that wouldn’t be okay if they were reliably reproducible.

- Wands. Ritualism is incredibly versatile, letting the wizard be a healer and a blaster and a controller and whatever else. Wands narrow that to (usually) just one task, but pay you back for it with a ton of extra throughput in that one task. It’s a way to support temporary specialization in a style of magic that is all about generalists, and we had many players pursue wand spells at top speed. These spells are also quite complex, requiring considerable planning to use properly.

- We did a few other things with spells requiring or benefiting from specific foci, such as foci with gemstones worked into them. This led at least one player to create a leather version of the Infinity Gauntlet; considering that the rep looked badass, we could hardly object.

- Regional spells. We staged two weekend events and one one-day in the setting’s northern reaches, never mind that it was summer and we were sweltering. The theme of the northernmost kingdom is Finland and its hero-wizards, so we drew on that by creating spells that only worked in specific game locations. Basically, the PCs could buy and use these spells for a few events and get a big power boost, but we didn’t have to deal with them as a normal part of game balance. The PC interest in these was a little less than I would have expected, but that was fine.

- Praxes. A praxis is a series of spells intended to be cast together, simultaneously or in series. We had interlocking runes (so you had multiple caster teams coordinating) in some cases, and effects that you had to sustain from beginning to end in others, for the rare and showy kind of ritual. At this point I wish we had done a little more with this. The thematic benefit of a praxis is that it gets the game’s top ritualists – who are in competition with one another for everything – to work together, or lose out on the coolest opportunities.

- Sure, if you have a full cabal of nine master wizards, you can do just about anything without cooperating with other teams. No one ever achieved that state, of course.

- Existing conditions on the caster change the resulting effect. Sometimes having a Soul Mark is useful, sometimes counter-indicated.

- Variable Fatigue – base cost of x, pay more to gain an additional benefit (such as twice the number of activations).

- Material components, and particularly scaling effects by the material component you choose – changing the Source of the spell from Storm to Fire OR Shadow, and then to Arcane, is sometimes pretty useful.

We also had hooks we never got around to using (that I recall – the list of spells is immense and I might have forgotten some):

- The total value of all pips in a spell must be greater than n or less than n or exactly equal to n.

- For every null face used in the ritual, gain or suffer some additional effect.

Here again, I think there were more unused ideas, but they escape me at the moment.

Challenges

The system has some elements that make it difficult to work with. While I don’t get much joy out of speaking ill of this creation, full disclosure is best.

- Creating all of these rituals is an overwhelming amount of work. Don’t try to do it all before the start of play – leave lots of room to expand the content as you go. (Do this with other skills too.)

- The wizards go dark for an hour or more at the start of play, and at whatever point in the game their Fatigue resets (if your game has a single, universal reset time). It is not plug-and-play friendly.

- The system works for solitaire wizards, but it doesn’t work as well. On the other hand, they can probably find a cabal looking for another member, even just a provisional member, without too much trouble. That worked itself out in Dust to Dust, at least.

- Because wizards are locked into their spell selection once they spend their Fatigue, they wind up either:

- Reserving a lot of Fatigue for unexpected problems that require spells they wouldn’t normally cast, or

- Having no way to use their primary skill to solve problems that they didn’t anticipate.

- One likely solution would be some way to “sell back” activations they had not yet expended. This was available, if difficult to attain, in DtD; it’s just as well that it wasn’t heavily used, because it presents significant design problems for some types of spells. (Orphan spells and wand spells in particular. Working backward to figure out the if/thens you haven’t triggered is a pain.)

- An alternate solution would be mechanics (perhaps consumable items, I dunno) to refresh Fatigue, but you’ve got to attach just enough sting to that cost that players treat it as a Sometimes food. Approach with caution.

The Future of Ritualism

Thus far, I know of five different LARPs that have lifted this system in whole or in part, and one of them has added a poker-based style to make Deadlands-style hucksters manageable in a boffer LARP. I’m thrilled to have contributed a set of ideas to LARPing as a broader form. I think there’s also room for a system that uses (larger, less easily to lose) bones as treasure, such that maybe I find a 2|5, a 1|6, and a 0|3 bone as the loot from an adventure, and I spend them along with your 1|2, 3|5, and 6|6 bones to do something cool. It would be a lot of prop-creation work overall, but remembering all that Shattered Isles did with Sculpey, it’s within reason and would probably be really memorable. (Also you wouldn’t be constrained to 0-6 or 0-9 faces – or for that matter even rectangular shapes.) This would be particularly ideal for an archaeology-related system.

You know, I think Eclipse is already doing something like this with their genetics system, and I just haven’t paid attention to it because I’ll probably never get Med Tech 10, much less the rest of the prerequisites.

I hope this post is useful to others planning to write and run boffer LARPs, to explain some of why DtD’s ritualism works the way it does. If you have questions, I’m happy to answer them.

First let me say this is brilliant. I am helping run a lap in upstate NY and we inherited a bad system for sorcery. The entire games economy revolves around collecting components to do the next augmentation ritual. This page helps make sense of the rules since I have never played dust to dust, but I get the impression that I am still missing a lot. I would love a complete copy of the rituals that were used in dust to dust and beyond that would be willing to discuss LARP design if you are willing.

Best Regards,

Story

I’m always interested in discussing LARP design and our ritualism system. We created a huge number of rituals for this system – I’m going to casually guess 125? – but I’m happy to share what we did and talk about what I’d consider doing differently if I had it all to do over again.