This post is a compilation and expansion of ideas first discussed in a series of Twitter threads, initially in response to a thread by Enrique Bertran, the NewbieDM, from October 25, 2018. I’ve returned to the idea in a number of threads since then – you’ll notice that I go from “I haven’t played Tomb of Annihilation” to talking about what I learned from playing Tomb of Annihilation. As of current writing, I haven’t played Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage, but I’ve heard people comment on experiencing dungeon fatigue there, so I’ll talk about that some too.

(One reason I’m posting about this now is to preserve these threads, in case the bird site suddenly goes away.)

October 2018

To which I replied:

This is one of the few times I’ve heard someone talk about the fatigue of long-term dungeon runs. In this thread, I’m thinking about causes and solutions. I’m not in the described campaign and haven’t played TOA, to be clear, so this heavy on speculation. What I am playing is Kainenchen’s dungeon-focused Liel campaign. We’ve played probably 10-12 sessions (?), and left the dungeon for the first time in the most recent session. We didn’t hit the point of fatigue, but I felt like it was a potential danger.

I’ve always found it tiring to READ mega-dungeons, especially because you see so many rooms that amount to another 4 goblins and a goblin alchemist or whatever. This room doesn’t have anything new to say compared to the room before it, but D&D calls for resource attrition. Speculation: the root of fatigue is that the tension stays steady – there’s much less of a sense of build-and-release. By contrast, the reason you can play an incredibly long campaign without fatigue is the tension cycle of goal completion.

In Liel, we established a home base area within the dungeon, much like a home base town in a wilderness hexcrawl. Returning to that barracks room after reaching a goal or calling a retreat was our tension relief. It wasn’t 100% safe, but the DM only threatened it once. Even then, we saw the same set of rooms a lot. I felt so outclassed that there was a strong urge to hunker down, play defense – which would have been terrible in actual play. Instead, things got a lot worse and we all got killed and eaten by a sentient dagger.

In our next session, we were spirits inside the dagger, which was a “dungeon” in its own right. This sense of shift, of changed context, also reduced fatigue. It also gave us a new short-term goal (come back to life), so a new sense of drive. When we completed that goal, what I said to Kainenchen was that I wanted to leave the dungeon and come back. I couldn’t explain at the time why that felt important, but part of it was that staying in the dungeon eroded the sense of the wider world as a context for our adventures. We left the dungeon for a few days of R&R, and to sell off treasures and spend the accumulated money. It was a palate cleanse session, and when we went back to the dungeon, we had a whole new list of goals and sense of renewed energy.

For another example, a campaign I played in 3.5e had us in a dungeon for many months of biweekly play. The fatigue was real by the end, made worse by not having a map connecting the areas we had explored. It felt disconnected, dreamlike. I don’t remember now if we knew what our long-term goal in that dungeon was, or if we just went in with a directive to explore to the end. I think there was probably a MacGuffin we were chasing.

If this were real, that sense of fatigue, of strain over an extended time, would be a key part of the emotional experience of the dungeon. It doesn’t interact in the right way with roleplaying bleed, though. The player doesn’t have constructive response options. What should happen, what I think people would do if this were real, is to seek emotional relief and reassurance from their companions, much like the core gameplay scenes of Ash Kreider’s The Watch. These are chances for interpersonal context to shift.

There’s a lot of pressure not to do this in D&D, to jump right back to the action after the minor logistical sequence of a long rest. Most of the time, this is fine and good, because the group doesn’t need a release and context shift. The actual play podcasts I listen to spend a lot of their runtime on small interpersonal scenes, which fascinates me for game-running and what those games are teaching. I mean, it’s a trope in Critical Role, characters knocking on doors at bedtime.

Anyway, I’m writing a kilo/mega dungeon (actual size TBD). (Editor’s note, 11/21/22: That project hasn’t yet gone forward.) I’m planning for a lot of the interest and action to revolve around a home base that the PCs establish within the dungeon. They launch discrete missions into various wings of the dungeon, then return. I’m hoping that by doing that, and by having additional friendly NPCs to talk to there, I can mitigate the sense of dungeon fatigue.

“Dungeon fatigue” is a core gameplay mechanic and aesthetic choice in Darkest Dungeon, and you mitigate it by making camp and having the characters take care of each other. In a sense, that care is a curiously heartwarming part of a soul-crushing game.

July 2021

In this thread, I’m talking about lessons that gaming can take from dungeon-heavy prose fiction. I’m using bullet points to make it a bit easier to follow the organization of the thoughts.

I’ve recently read Gideon the Ninth, Piranesi, and Starless Sea, all of which have dungeon-crawl sections. I think there are some cool lessons we can take from them for #dnd and other TTRPGs. They all do something different, and translate into gaming in different ways. There are going to be spoilers in this thread. You have been warned.

- In The Starless Sea (an intensely gaming-aware narrative… the main character is majoring in gaming), the dungeon is full of symbolic things, clues to a greater story, and doorways to Elsewhere. No combat, but Investigation challenges with a loose sense of time pressure.

- To bring this into D&D, where combat is part of the fun, use the dungeon as an interstitial space. It’s a home base that has only symbolic threats, but new rooms to unlock & clues to find. When you leave the dungeon through any of its doors, fights are back on the menu.

- As an aside from the dungeon-y parts – the “team” of this book is three characters, with very different levels of information about what the hell is going on, and goals that are mostly about each other. Do that.

- Piranesi is a dungeon with one protag, Piranesi (eventually joined by one supporting character who could be someone else’s PC that joins the campaign late), and one antagonist. The dungeon is mostly empty, and loneliness is the predominant mood. Piranesi explores and faces traversal challenges (dangerous climbs and leaps), keeps himself fed, and finds clues about what’s going on that are WAY outside his frame of reference.

- In addition to hunger and thirst, the dungeon costs him memories, creating time pressure.

- Traversal challenges are a bit hard to sell in D&D. The tension of a single Strength (Athletics) or Dex (Acrobatics) check is not super interesting as something to roll each time you need to go through a certain area, and teleportation/flight are common workarounds.

- You can emphasize the decay of the architecture through repeated passage. Failed checks both cause the PC to take some damage and increase the difficulty of later checks.

- Full-on failing the traversal is particularly hard to make interesting, since PCs have to retry.

- Managing the slow bleed of memories is another interesting game-running challenge, and one that Lee Hammock valiantly tried to tackle in a long-ago game concept. I think you want to lean into identity as the sum of the memories you retain. So you initially have, say, 5 core memories that define who you are. You can regain old core memories by re-reading old journals that you find, but at some time intervals you roll a saving throw to avoid losing a core memory. This strongly pushes player note-taking.

- The dungeon’s geography matters a great deal, with different regions becoming pseudo-biomes. The more remote and difficult-to-reach the area is, of course, the more valuable its resources, whether food or clues. But also the dungeon is infinite, as far as we know.

- It’s just that Piranesi instinctively stays sort-of-near the most interesting part of the dungeon. He does occasionally go a whole day’s walk in down one infinite hallway, then comes back.

- Gideon the Ninth: the one with (comparatively) lots of combat. There are no wandering monsters – or, well, the wandering skeletons are the staff, not threats. Other than some duels, the fights are boss-fight-level dangers, some with Zelda-style puzzle solutions. Those fights and puzzle rooms unlock new areas and teach the spellcaster new spells. The sense of “leveling up” is veiled in narrative, but not hard to find if you’re looking for it. And we LOVE achievement-based advancement here.

- Of these dungeons, Canaan House in Gideon the Ninth is the easiest to translate into D&D, by a long shot. Adding more fights while in the non-safe portions of the House would probably not damage the mood of paranoia and race-against-other-teams that the book goes for.

- There are two PCs at the start of the book, and two more (Camilla Hect and Palamedes Sextus) that join the “team” after a certain point in the book. It becomes clear that they’re not interested in competing for the “prize” of the “contest.”

Starless Sea solves dungeon fatigue by making the dungeon into the safe/home space. Piranesi “solves” it by giving the protag literally no concept of a space outside the dungeon. That might be a harder sell for your players. Gideon the Ninth alternates between dungeon “runs” – that is, the team sets one specific goal and pursues it, then comes back – and escalating-stakes, tense social scenes. But it’s clear from the start that no one is going home until someone “wins” or everyone dies.

At a gaming table, I think you’d want to try to fit in one dungeon run AND one social scene per session, really leaning into that sense of narrative loop to help each session feel satisfying. It’d be similar to the adventure + Winter Phase loop in Pendragon, basically.

March 2022

I wrote the following thread after our third session in the actual Tomb, in our Tomb of Annihilation campaign.

The key dungeon design note I’ve taken from Tomb of Annihilation so far (no spoilers): Create areas of heightened importance within the dungeon, and sell their importance well before the PCs get there. Completing those areas feels meaningful and reduces dungeon fatigue.

Conversely, a lesson I’m struggling with as a PC: you don’t have to 100% clear the dungeon. It’s okay for PCs to opt out of some major rooms, and to consciously design for them to do so. I’m here to see content, but our overall success will require taking fewer chances.

In an old-school treasure->XP model (not what we’re using), you want to skip fights as much as possible, but treasure is king. We’re milestoning it (Editor’s note: this was my impression at the time; turns out the DM was tracking XP behind the curtain), and we have 5e’s limited attunement slots. Conclusion: some percentage of those important rooms offer us nothing but a chance to lose.

If this is all obvious to you, cool! I have been a player in two (2) megadungeons over the last 29 years in the hobby, both operating on very different design principles. No one taught me this, and this is my first hard-won experience with this approach. In all honesty I still wouldn’t Get It if another player in the game weren’t pointing it out. The completionist mentality has been hammered into my skull much, much harder than any other. Well, that and stinginess with consumable items!

November 2022

I wrote the following thread after we had been done with Tomb of Annihilation for several months and moved on to the next campaign.

This isn’t revolutionary or anything, but I think that for me one of the best ways to build a kilo/mega-dungeon might be to build a series of five-room dungeons, each with their own contained story. Then hook them up with hallways, portals, other transition spaces.

I’ve talked before about how megadungeons need to get broken down into clear, achievable goals. If you know that Ganon is somewhere in this 100-room dungeon, but that’s all you have to go on, the dungeon fatigue is going to be brutal.

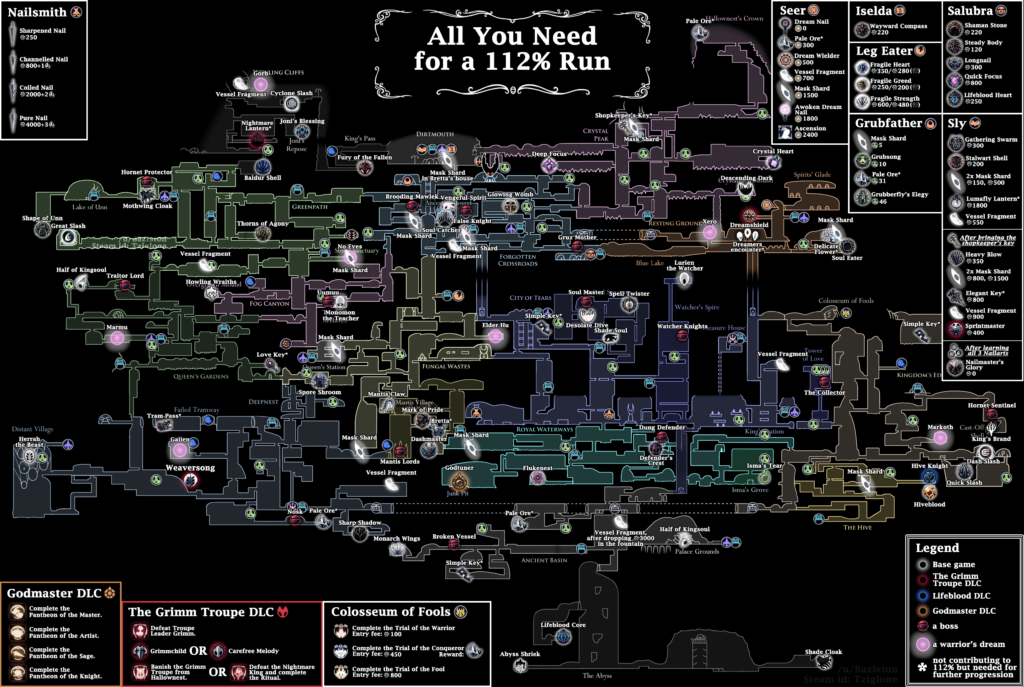

Instead, you take 2-5 of these five-room dungeon clusters and give them the same dungeon “biome.” If you’re building a kilodungeon (many sessions of play but less than the whole campaign), job done! The transition from cluster to cluster and biome to biome picks up a lot of significance. See the Hollow Knight map, above. Biome shifts are also a great moment for changing the environmental rules – see Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything, Chapter 4: Supernatural Regions.

In addition to the sense of completion for the players, the other benefit is that I find I can stay more interesting if I am thinking five rooms at a time, because I’m less inclined to save the story reveal for 20 rooms from now. It also pushes me to make up more secrets.

Like I said, not revolutionary. But breaking stories up into smaller pieces – and planning how each of those pieces changes when your players come back through – may help you get your head around the monumental task of writing and running a megadungeon.

Here end the threads.

Synthesis

The core idea of these threads is that pacing needs active management and intentionality in a megadungeon, maybe even more than in non-dungeon play. I know a lot of groups that steer clear of large dungeons in 4e and 5e play. While I don’t know everyone’s reasons for doing so, I think a lot of it is dungeon fatigue – DMs who haven’t developed techniques for keeping room-by-room exploration and clearing engaging, session over session.

Focus on:

- Giving PCs clues about rooms they haven’t seen yet, or new ways to engage with already-explored rooms. Don’t hesitate to give PCs incomplete maps – or complete maps with no information about encounters or treasure.

- Giving PCs levers to alter the dungeon

- Opening new routes (shortcuts, secret areas, treasure rooms). One of the most thrilling moments in Portal and ToA alike is when you get somewhere that the dungeon-builder doesn’t want you to be.

- Turning off lair actions, legendary actions, or other overwhelming problems. Flooding a level, or draining a flooded level, is a classic for a reason. My imagination finds something striking in PCs being a major force for entropy in a closed environment, such as a dungeon.

- Changing difficulty (of combat or traversal scenes), or making a dangerous area safe to rest

- Discrete goals and stories that can be introduced and resolved in a single session of play

- Varying encounter types as much as possible. Multiple combat encounters in a row becomes grindy for many groups – part of why I think people favor non-dungeon play is that they instinctively include more social and exploration/investigation play.

- A dungeon that poses interesting questions – something other than “are we there yet?” Why is this weird device here, what purpose does it serve, will it help us or destroy us? The best case is when answering one question immediately raises two more.

From reading Dungeon of the Mad Mage, I think its core problem is that too many people expect to press straight through the dungeon in a single delve, rather than making regular returns to the surface. The mechanics of the portals – the way you can skip levels and get back to where you left off – are punitive, and I think that’s inappropriate to the situation overall. I also think the individual levels of Undermountain need more contained stories within each level, in addition to each level being a story.

See Dead in Thay for a way to do what I’m talking about – in a response to my Twitter thread, Scott Fitzgerald Gray says that the cluster of 3-5 rooms was the core design unit of the Dead in Thay dungeon, which you can find in Tales from the Yawning Portal.

I hope these ideas are useful to you in your own dungeon-building. Which isn’t to say that every session should be in the dungeon! Only this: a lot of what Jennell Jacquays developed in the earliest years of the hobby got lost in the time since, and this blog post winds up being a discussion of why her innovations were important.

There are some interesting points here about the modern take on the megadungeon. Having run the ToA, I can say that I was experiencing dungeon fatigue by the end of the module. I think a huge part of that is that ToA isn’t designed like a “traditional” megadungeon. The story of the module makes it imperative that you don’t stop or slow down, you aren’t encouraged to leave once you get into the dungeon proper. Never mind that the ticking clock in ToA is so fast that everyone affected by it dies before you get anywhere near the actual tomb.

To me, a megadungeon is something that you take time to explore, doing multiple delves over the course of months of in-game (and real-world) time. You do other things in between each delve, some other type of adventure. The dungeon changes between delves, it’s never exactly the way you left it when you come back. This can mean that areas you cleared previously need to be cleared again. Megadungeon play rewards familiarity with the dungeon. ToA doesn’t do any of this, it’s effectively a very large “regular” dungeon. The way it is written it expects you to go from top to bottom in a single delve, finding one of the three or four places you can rest to regain your abilities as you go.

The other major basic hurdle to megadungeon play in 5e (and 4e) is that modern DnD doesn’t really have any guidance for procedural dungeon exploration or management. I had the misfortune of finishing ToA about 2 weeks before discovering Old School Essentials. If I had found OSE first my ToA game would have played very differently than it actually did. I would love to see some official support for megadungeon play, but I doubt very highly WotC will ever produce anything like that ever again.

I agree with your points about ToA – our DM reworked the Death Curse to not start its timer until we were in Omu, so my experience of that aspect was more positive. From what I understand this is a fairly common change, and I recommend it highly. ToA is very much unsuited to a multiple-delve approach.

I’ve still only read the OSE free starter, which is the least interesting or helpful part to me (having never been enamored of race-as-class). I expect I’ll pick up a full copy sooner or later, just to see what else it has to offer. You are likely right about there being no future official megadungeons (certainly not any time in the next several years), but third-party megadungeons aren’t a dead concept. I have some plans that I might eventually be able to bring to fruition…

I recommend OSE as a game design resource if nothing else. Race-as-class is the default assumption, but the full rules at least also include race AND class as an option. I personally think the best part about the system (and the part that is most applicable to other editions) is the various rules for procedural exploration play, both in wilderness and dungeon environments. I had heard of the concept of a “dungeon exploration turn” before but had never really understood how that was organized or what it might look like in play.

I do hope 3rd parties continue to support megadungeon play, both with the dungeons themselves and with rules and advice to run them smoothly. Fatigue builds way faster when you are having to blunder through the running of something complex because the provided text is lacking in direction. Kobold Press recently released their Scarlet Citadel, which I believe they billed as a small megadungeon. I’ve been following your entries on your Ruby Talon dungeon with interest, it would be cool to see that turn into something polished for publication.

You’ll be seeing more of the Ruby Talon Deeps development-in-progress before long, I’m sure. I’m the kind of writer – as you’ve probably figured out by now! – that always has twenty ideas on a back burner at once, and only occasionally gets one all the way to print. On the plus side, that means in this case that the Ruby Talon Deeps dungeon is only one of three different megadungeon products I’m working on!